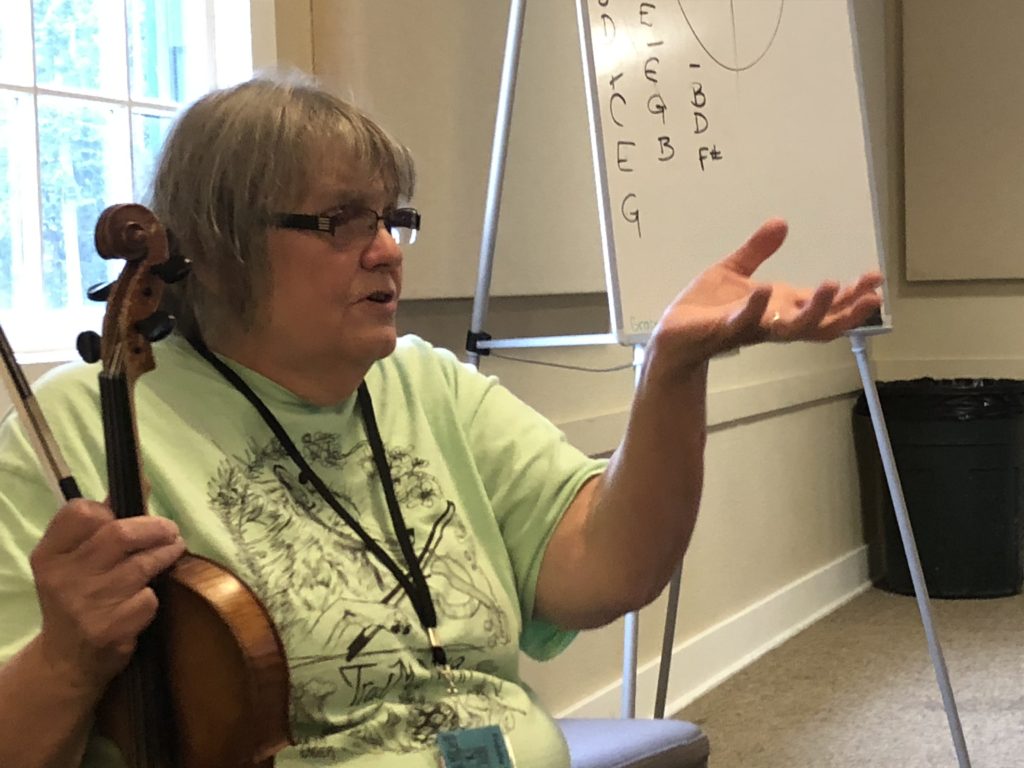

My teacher didn’t like the instability of my bowing. It tended towards crooked (as in not parallel to the bridge), and with the hair on an angle to the string. The resulting sound was thin and reedy. I was usually unaware and unable to correct the problem. He prescribed the following prescriptive exercise on open strings: A simple detaché stroke, using only the forearm.

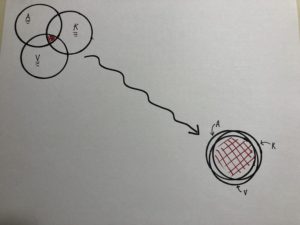

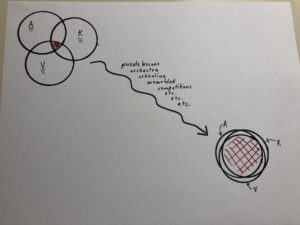

In this exercise I am to stabilize my shoulder, upper arm, wrist and fingers, and move only my forearm, and only within the range that the bow remains parallel to the bridge. The idea is to isolate a single movement and create a muscle-memory of where the right-arm-and-hand exist in space during this simple bowing motion.

Arm weight is in the string. Hair is flat on the string. Strings are open. Sound is full and ringy. I do this exercise for several minutes daily, working to (1) develop a physical feeling of where my arm is in space when the sound is best; (2) develop an ability to return my arm to this place when the sound is off; (3) develop a level of comfort such that any other place for my arm feels like a deliberately chosen aberration, rather than a place it ended up unknowingly by accident.

I open every practice session with this exercise, and return to it whenever my bowing goes wonky. I do the forearm exercise before playing a piece. And also frequently before playing each phrase when I break down a piece. I do this exercise a lot, seeking a level of physical ease and comfort and sonic fullness that come automatically. Seeking muscle memory.

The exercise becomes meditative. To add complexity, I add string crossings. At the next lesson my teacher asks for the same exercise, but with a martelé stroke. The position and the motion of this exercise will become “home base” for bowing, out of which all further complexities of bowing will emerge, one simple step at a time.